The effect of Open Data on Citations

We here provide some idea of what it would take to try to infer the causal effect of one specific Open Science practice on citation impact. In particular, we consider the effect of Open Data on citation impact. That is, papers that share their data might be more likely to be cited. This is something that has been called the “Open Data Citation Advantage”, and in the PathOS scoping review of the academic impact of Open Science (Klebel et al. 2025), evidence was found for a small positive effect of sharing data.

Inferring the causal effect of open data on citation impact is not straightforward and cannot easily be done in an experimental setting. Although an experiment study could in principle be done, it would require researchers to participate and follow the experimental, randomised “treatment” of sharing data or not, which will be challenging, especially where more and more data policies mandate that data should be shared. This means that, barring such experiments, we have to rely on observational studies of citations to publications that have (not) shared their data. Note that we here only focus on whether data was shared or not, not whether the data is FAIR or not, or the extent to which it is FAIR, although that might be a relevant confounder to consider.

We will try to produce a relevant structural causal model by going through the following steps for determining what are relevant aspects for studying the effect of open data (X) on citations (Y).

- Consider causal factors that affect or are affected by X or Y

- Consider effects between the identified factors.

Let us start by considering factors that have a causal effect on the number of citations to a paper. As suggested above, there are many factors that correlate with citations (Onodera and Yoshikane 2015). The scientific field and the year of publications are two very clear causal factors, and are usually also considered when normalising citations. One other relevant aspect is obviously something like the quality or relevance of the research: higher quality or research that is more relevant to more researchers, will be more likely to be cited. Unfortunately, such a quality or relevance is not directly observable. Where something is published, i.e. which journal, is likely to have a causal effect on the citations (Traag 2021). In addition, there are most likely some reputational effects of the author and the institution (Way et al. 2019). Finally, (international) collaboration might be likely to have some effect on citations as well, potentially mediated by network effects.

Let us then consider factors that have a causal effect on the sharing of open data. One clearly relevant factor is the open data policy of the journal where the publication is published: if a journal has a clear open data policy that requires authors to make data available (e.g. PLOS’ Data Policy), publications in that journal might be more likely to be make their data available. Similarly, if research is funded by a funder that has a clear open data policy (e.g. Wellcome Trust’s Data Policy), the data might be more likely to be made available. Funding might also make it more likely that authors make their data openly available due to an increase in resources (e.g. data support). Similarly, institutional resources (e.g. data support or training) might help make data open. Some fields may have an academic culture in which scholars are more accustomed to making their data openly available. In addition, some research approaches in a field might be more likely to make their data available than others (e.g. it might be easier to share anonymised quantitative data from surveys as opposed to thick interview data). Lastly, open data has increasingly become a standard, meaning that more recent publications might be more likely to share their data.

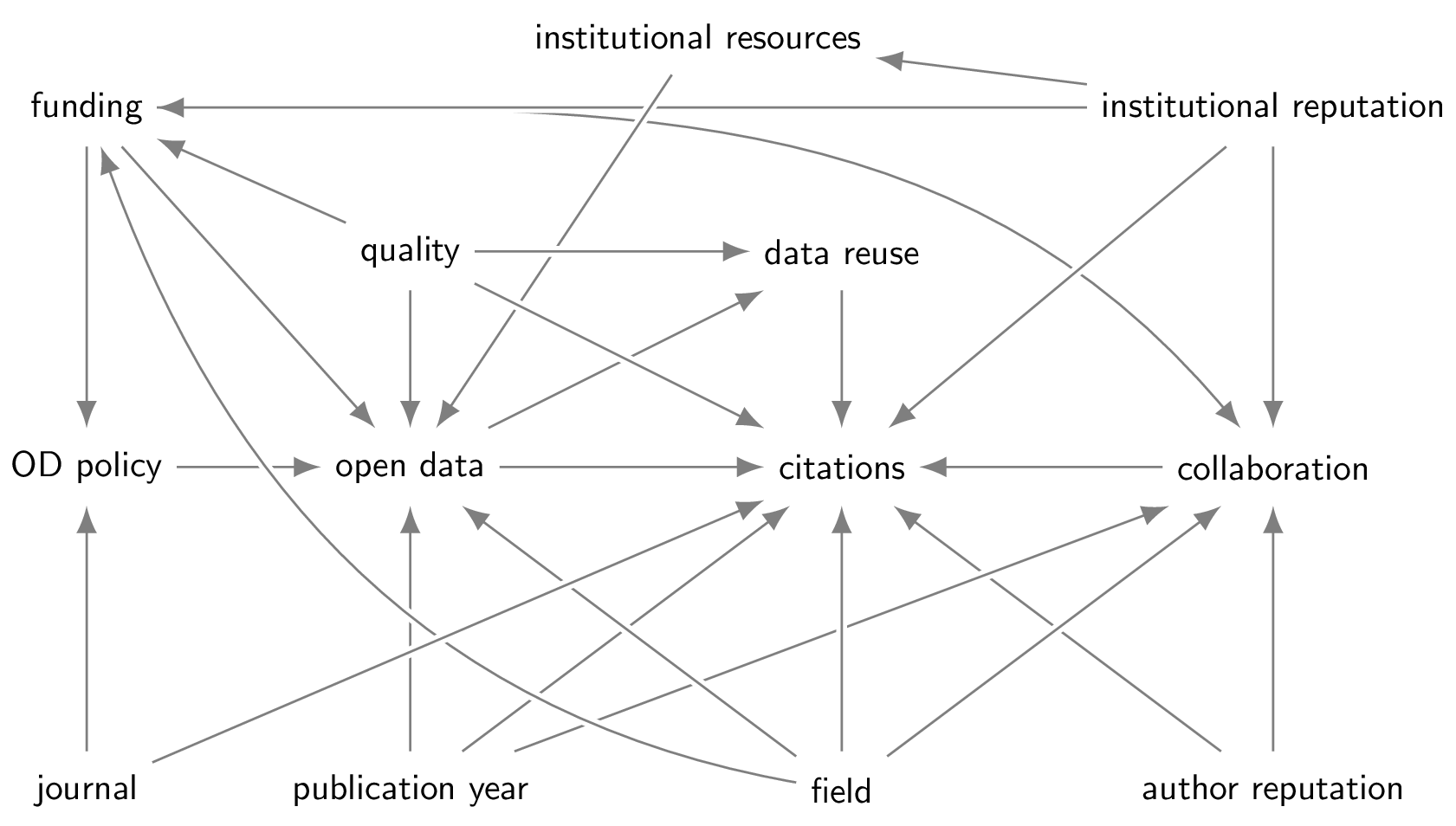

We can now consider the interactions between the various factors mentioned. For instance, institutional reputation is most likely to be associated with institutional resources (with the causality arguably going both ways dynamically over time, being mutually reinforcing). As another example, in some fields of science collaboration is more common, and reputation effects probably also play a role in collaboration. There are many other such examples. All considering, we then arrive at a structural causal diagram such as below.

Many of the mentioned factors are confounding factors for identifying the causal effect of open data on citations. In addition, some variables function as a mediator, in particular, data reuse is likely to be a mediating factor. Some variables can also act as a collider (e.g. funding), so we should make sure to consider this when controlling for certain variables. For more background reading how to do this, see the causality introduction.

There are two causal paths, one direct (Open data \(\rightarrow\) Citation) and one indirect (Open data \(\rightarrow\) Data reuse \(\rightarrow\) Citation). All other paths are non-causal. There are various ways in which we can control for factors to identify the causal effect of open data on citations. You can identify all possibilities automatically, for example using https://dagitty.net/. One possibility of controlling for the necessary factors to identify the causal effect is the following: we control for journal, publication year, field, , funding, institutional reputation and quality. This closes all non-causal paths, and leaves open the causal paths. All of these controls are reasonable, except “quality”, which is not directly observable. Although we can use something like peer review to assess quality, it might suffer from biases that prevent us from effectively controlling for “quality”.

When we consider the analysis by Piwowar and Vision (2013), we see that they indeed control for all mentioned factors, except “quality”. They also condition on a number of other factors. This includes collaboration, but according to our causal diagram, this is not necessary after controlling for publication year, field and funding. Missing from our causal diagram are country level effects that Piwowar and Vision (2013) do consider. Although this could be relevant to consider in the structural causal diagram, we are unsure what the causal pathway would be. One possibility would be a country-level citation effect, but countries might also differ in their data sharing infrastructures (e.g. repositories) or policies or support (e.g. data training), which might need to be considered further.

All in all, the analysis by Piwowar and Vision (2013) seems to control for all necessary factors, except “quality”. They estimate that sharing data increases citations by about 9%, while about 6% of the citations concerned data reuse, suggesting that roughly two thirds of the increase would be mediated by the data reuse. Their estimate of 9% is most likely an upper bound, since part of that estimate is still confounded by “quality”. That is, the confounding effect of quality will most likely result in an upward bias: quality increases both citations and open data. This is indeed consistent with the possible reason of “selection bias” that is mentioned by Piwowar and Vision (2013, 20), but they seem to interpret this as a causal explanation, while we would not interpret this as a causal effect, but as a confounding effect. The other suggested reasons for the open data citation advantage include “credibility”, “visibility” and “early views”. We have not included them in the structural causal diagram as specific factors, but the diagram could be refined to also include those factors.

References

Reuse

Citation

@online{apartis2024,

author = {Apartis, S. and Catalano, G. and Consiglio, G. and Costas,

R. and Delugas, E. and Dulong de Rosnay, M. and Grypari, I. and

Karasz, I. and Klebel, Thomas and Kormann, E. and Manola, N. and

Papageorgiou, H. and Seminaroti, E. and Stavropoulos, P. and Stoy,

L. and Traag, V.A. and van Leeuwen, T. and Venturini, T. and

Vignetti, S. and Waltman, L. and Willemse, T.},

title = {Open {Science} {Impact} {Indicator} {Handbook}},

date = {2024},

url = {https://handbook.pathos-project.eu/sections/0_causality/open_data_citation_advantage.html},

doi = {10.5281/zenodo.14538442},

langid = {en}

}